THE DOVER COUNTY SCHOOL 1905 to 1931

The School known since 1944 as The Dover Grammar School for Boys

By K. H. RUFFELL, B.A.

who taught in the school 1937-40 and 1946-79, formerly deputy headmaster and currently editor of The Old Pharosians' Newsletter

FRED WHITEHOUSE 1st Head

THE DOVER COUNTY SCHOOL 1905-1931

Preface

Now eight years into retirement, I have been closely associated with the school and the Old Pharosians since first appointed to teach at the Dover County School in 1937, fifty years ago. I have had contacts with Old Pharosians of every age, most valuably for the present purpose with those still living who were at the school in its early years and can contribute those human stories and impressions that add living interest to factual records stored in dusty volumes.

By kindness first of the Archivist’s Department at Maidstone and then of Folkestone Public Library, the Minutes of Dover Education Committee from 1902 to 1910 have been made available. From 1908 onward the school magazine, The Pharos, is rich in representation of the life of the school. Perhaps editors of today and tomorrow may be encouraged by the idea that they are recording history.

I am well aware that in The Pharos of 1965 at the time of the school’s Diamond Jubilee, Miss O. M. Rookwood wrote about the period 1905 to 1946, and Mr. E. W. Lister, the school’s senior history master in 1965, wrote of the continuing period from 1946 to 1965.

This present account hopes to supplement and in no way replace Miss Rookwood’s history. She taught in the school from 1917 to 1942, followed by some part-time teaching in the immediate post-war years, and her devotion continued as long as she lived. I have had access to individuals and records not used previously, and all writing is characterised by personal interests and contacts. I have too much respect for the memory of Miss Rookwood to hope that I can do more than complement her account.

Among the Old Pharosians who have been most helpful are:

Mrs. L. Turnpenny 1905-12

Mr. E. H. Baker 1922-38

Mr. G. Curry 1927-36

the late Mr. A. Gooding 1905-09

Mr. A. H. Gunn 1918-24

Rev. W. A. Law 1915-20

the late Mr. N. V. Sutton 1909-12

Mr. G. Took 1908-11

Mr R. J. Unstead 1926-34

Mr. R. C. Wilson 1905-12

Sincere thanks are expressed to these and many other Old Pharosians; to our historian headmaster for his encouragement; and to my wife for typing the manuscript.

Finally, the Old Pharosians’ president and committee gave their blessing and support to the publication. An anonymous Old Pharosian generously promised to relieve us of financial pressure and Buckland Press has dealt speedily and efficiently with the processes of publication.

K. H. RUFFELL,

June, 1987.

THE DOVER COUNTY SCHOOL 1905-1931

CHAPTER ONE

The Educational Scene in Victorian and Early Edwardian Times 1850 to 1905

We may begin by surveying the educational world into which was born the Dover County School in the opening years of the present century.

Fifty years earlier a conference on the nation’s education, presided over by the Prince Consort, had surveyed the state of education; and a royal commission considered “the extension of sound and cheap elementary instruction to all classes of the people”.

Hitherto schooling bad been mainly restricted to a privileged minority by church schools, the few “public schools” and the endowed grammar schools. Voluntary elementary schools provided by the churches could not possibly educate the whole youth of the nation so the state rook over this task, providing schools and helping to maintain the churches’ voluntary schools. With an eye to efficiency a system of “payment by result” was instituted and practised for thirty years. It cannot have been much fun for teacher or taught.

Mr. Forster’s Education Act of 1870 established the intention to provide elementary education for all, having observed that some European countries were ahead of our own in this respect. Board Schools were to be financed by the rates; and there followed a competitive building programme between church and state. But not until 1880 were there enough schools for compulsory schooling to be enforced by school attendance officers.

In Dover many of the present schools date from this late Victorian expansion of educational provision, Previous education in the town had been mainly church provided; and until the 1960s there was in the centre of Dover a church school in which were two gallery classrooms, each seating some fifty-five pupils, supervised by one teacher assisted by pupil teachers. In schools of this type pupils worked their way, according to examined progress, from standard one toward standard seven. Many tales have survived of methods to deceive examiners into the award of passes which produced money.

In 1895 there was in Britain one certificated teacher, college-trained for two years, for every hundred pupils. Trained teachers were assisted by uncertificated teachers and pupil teachers, aged between fourteen and eighteen years, the whole teaching force yielding an average of one teacher per fifty pupils.

Parents who could afford to pay fees and who regarded the public elementary schools as unsuitable would send their young children to private schools where ladies conducted lessons in their own houses. Most of the early intake into Dover County School came from this kind of private primary school.

Some headteachers received £300 a year, the figure which the young Mr. Whitehouse received in his early years in the Dover County School. An assistant teacher would have a salary in the region of £100 a year, perhaps more for a man, probably less for a woman. Church voluntary schools tended to pay less than the Board Schools funded by the rates.

In spite of high infant mortality, child population rose rapidly. By the end of the century “payment by results” had been abolished and new ideas were introduced, new subjects and methods were attempted, new amenities provided and evening classes were well attended. On occasion, grandfather and grandson sat side by side learning to read and write.

Particularly strong was the demand for technical education because great industrial exhibitions in Europe and America showed that we British were losing our early advantages. Money was made available from the Department of Science and Art in South Kensington which made grants to schools prepared to teach appropriate subjects. Some of the elementary schools became higher grade schools.

In Dover a Technical School had been started in 1870 in Northampton Street. In 1883 the Connaught Hall, beside the Maison Dieu, and other municipal buildings were opened. During the following year educational premises were added in Ladywell at the eastern end of the municipal buildings and the Technical School moved in, as is recorded on an engraved stone in the Ladywell wall commemorating the opening in 1884.

In 1900 some of these premises were set apart for a Municipal Secondary School and Pupil Teacher Training Centre. in these same rooms technical education is continued at the present time.

The church schools and board schools continued to provide elementary education; but some boys and girls desired secondary schooling, in some cases with a view to becoming teachers. Pupil teachers would divide their time roughly equally between assisting the teachers in elementary schools and attending lessons in Ladywell preparing for admission to a training college, hopefully helped by a Queen’s scholarship.

The Municipal School, the Pupil Teacher Training Centre and the Technical School were not the only places in the area offering secondary education. Dover College, founded in 1870, was a Victorian representative of the fee-paying public schools whose emphasis was on the teaching of the classics with a view to university entrance and the professions. In Folkestone was the Harvey Grammar School where a 17th century benefactor, educated at the King’s School in Canterbury, left land to finance a school in which boys could "learn English and, if they wished, Latin”. In Dover there was a fee-paying High School for Girls: and boys and girls were on an equal footing in Dover’s Municipal School and Pupil Teacher Training Centre. By this time universities and colleges had opened their doors to women and awarded degrees. One lady, Mrs. Turnpenny, still resident in Dover in 1987, recalls the earliest days of the Dover County School, from which she went to Bedford College, London and graduated.

Turning the pages of history from one century to another can give rise to new thought and action. The Boer War, like later wars, provoked hopes for a "land fit for heroes” in the subsequent peace.

The county councils and county borough councils had been established since 1888 as the providers and controllers of elementary schools and such public secondary schooling as existed. A legal judgment that threatened to cut off funds from secondary schools led to the Balfour Education Act of 1902, which Act we can regard as occasioning the conception if not the birth of the Dover County School. In parliamentary debate it was said, "The very existence of the Empire depends on seapower and schoolpower.” The new century brought new life to English education. Part of that new lift was the union of the Dover Municipal School with the Pupil Teacher Training Centre to give birth to the Dover County School for Boys and Girls.

Reference may be made to The Silent Social Revolution (1969) by G. A. N. Lowndes (O.U.P) obtainable through Dover Public Library.

CHAPTER TWO

Birth Pangs

1902 to 1905

Kent County Council was the authority required by the 1902 Education Act to provide and maintain secondary schools in Dover. In the Ladywell premises were the Borough’s Municipal Secondary School, the Pupil Teacher Training Centre and the Technical School of Science and Art. Kent Education Committee decided to take over these establishments unless existing managers desired to retain control. Neighbouring Canterbury ranked as a county borough and continued until 1974 as the local education authority. The managers at Ladywell desired to retain control and Dover Council considered an application to the Board of Education that their secondary schools should be recognised under the 1902 Regulations. Further consideration, inevitably dominated by cost, led to the idea being dropped.

In the academic year 1902-03 the School of Art had 839 pupils at daytime and evening classes. The principal of the Municipal School was required to report on the proportions of scholars entering from public elementary schools and from private schools, and to submit a scheme for the establishment of scholarships for pupils from elementary schools. An H.M. Inspector reported favourably on evening classes in the Municipal School; and the principal agreed with the inspector that practical laboratory work should be given to pupil teachers on Thursday evenings by the science teacher, Mr. George Devenish Thomas, for which he would receive a fee of seven shillings and six pence per evening.

The principal at this time was Mr. W. H. East whose appointment began in 1870 with the foundation of the Technical School. He also did some teaching in Dover College.

During 1902 Mr. Fred Whitehouse, M.A. (Oxon), came to Dover to commence his work in secondary education. He very soon established his imprint that will never be removed.

In September, 1903, the principal of the Municipal School reported that admissions over the first three years of the school’s existence were as follows:-

from Dover elementary schools 28

from other elementary schools 9

and from private schools 53

so the school contained about 90 pupils, He recommended that three scholarships of values £5, £4 and £3, tenable for three years, be awarded annually to pupils of Dover elementary schools who had passed standard six and were recommended. He also suggested a leaving scholarship of £25, tenable for two years.

Mr. East also asked for a playground and was granted temporary use of land, now a car park, adjacent to the school. There was also access to what is now a bowling green, where boys and girls could walk, subject to a decree that fraternisation was forbidden, the girls to circulate in one direction and the boys in the opposite circum-perambulation.

In January, 1904, the Dover Education Committee formed a Higher Education Subcommittee and K.E.C. agreed to a proposal that the work of the Pupil Teacher Centre should be merged in that of the Municipal Secondary School. Mr. Whitehouse became responsible for the Secondary School at an annual salary of £200 while Mr. East was responsible for the School of Art and for the whole building.

To assist Mr. Whitehouse were

Miss Brown salary £110 per annum

Mr. G. D. Thomas salary £170 per annum

Miss M. Forster salary £100 per annum

Miss G. Chapman salary £70 per annum.

Miss Forster later became Mrs. G. D. Thomas; and Miss G. Chapman was sister to Miss Jessie Chapman, at that time head of St. Hilda’s private school for girls on Priory Hill.

Mr. G. W. Coopland, M.A. had been appointed in the previous year to teach English, French and history but he seems to have been at first on the staff of the School of Art. In 1904 Mr. Coopland succeeded in persuading his friend Mr. J. Tomlinson, M.Sc., to join the staff to teach mathematics. Mr. Coopland, nine years later, moved to Liverpool University where he taught with distinction and won great affection for the rest of his teaching career. Mr. Tomlinson stayed at Dover until 1938 when he was deputy head and head of mathematics. During his teaching career he followed a London University course in mathematics and Greek and obtained a B.A. degree in that study.

The pupil teachers continued successfully on their courses and formed their own association of members with Mr. Whitehouse as their head.

In 1904 there was even talk of the need for new premises in a permanent building; and the town clerk was asked to seek the county’s views if Dover provided the site. In this same year the pupil teachers gave a full choral rendering in the Town Hall of H. W. Longfellow’s Excelsior; and in 1905 Mr. Whitehouse could report that all twelve candidates for King’s Scholarships to Goldsmith’s College had been successful. In April, 1904 Mr. Whitehouse had been given an increase of salary in recognition of his extra services, an annual increment of £15 per annum to a maximum of £300.

There was a distribution of prizes in the Town Hall, a practice that continued until the outbreak of the Second World War and for a few years afterwards. The staff wore dinner jackets, academic gowns and hoods so the occasion was a full-dress presentation of the school to the town.

Evening classes continued under the direction of Mr. Whitehouse who also taught English literature. Other subjects were arithmetic, history, mathematics (for men only), psychology, theory of education (for women only) and geography. Most of the classes were held in Barton Road school and thirty students were essential for a course to function. Fees were £1 per term and there was a qualifying admission test.

The Ladywell premises were proving inadequate and eyes turned toward Miss Jessie Chapman’s private school for girls on Priory Hill. Miss Chapman had no degree or other qualification but K.E.C. took over her St. Hilda’s School with Miss Chapman as principal mistress, mainly used at first for pupil teacher training.

Reports were made on the numbers of students studying science, technical and commercial subjects. An additional mathematics class was started, probably due to the arrival of Mr. Tomlinson. When the school asked for playing facilities, arrangements were made for use of the Danes ground and Crabble Athletic ground.

In 1905 there was a flurry of re-organisational activity. Mr. Whitehouse, not surprisingly, applied for and was granted clerical help. He was given a bonus increase of £30 to his salary.

Inspectors discussed the existing amalgamation of pupil teacher training in the secondary school and they recommended the separation of boys and girls under distinct staffs. They also advised that division should be made between boys and girls on the play area, with separate entrances. The inspectorate regretted that there was no mistress responsible under the headmaster for discipline of girls. The school provided a four-year course but there should also be a preparatory class for children under twelve years. There was, noted the inspectors, no ceremony for opening the school day.

There was one deeply significant element in the report of the inspectors. It stated that Mr. East appeared to have no special qualification for a position in the secondary school. Both Mr. East and Mr. Whitehouse were required to give their views at a March meeting of the Dover Higher Education Sub-committee. This was done and Mr. East was asked to resign his overall direction when a new establishment should be set up after the summer vacation. Mr. East did resign from any claim to headship of the secondary school, and Mr. Whitehouse’s name was inserted as headmaster. Mr. East should continue as head of the Technical School, often known as the Art School, and he should have administrative management of the building but in no way was he to interfere in the internal management of the Secondary School.

The county, subject to minor alterations, officially approved the merger of the Pupil Teachers’ Centre with the Secondary School, together with the addition of a preparatory department.

In June the resignation of Mr. East from any position in the Secondary School was accepted. The Dover Education Committee expressed their high appreciation of the great assistance he had rendered in commencing and conducting the Technical School over twenty-eight years and they recorded their thanks for his services.

From this time Mr. Whitehouse alone attended meetings of the Higher Education Sub-committee. Mr. East continued to send estimates for the needs of his area of authority. The two men jointly recommended in July that £100 be spent on the playground.

At a conference with a County Inspector, Mr. East presented a report on the Technical School and evening classes for 1905-06; while Mr. Whitehouse made suggestions for the Secondary School.

There was a proposal that Mr. East’s salary should be £567 but the county cut this to £500. This reduction after twenty-eight years of service was accepted under protest by Dover.

Mr. Whitehouse was strengthening his staff by the appointments of Miss Jones, Miss Hilda Watson, Mr. Frank Smith, B.A., and Mr. Standring. We see Mr. Standring in school team photographs for many years.

A new prospectus was prepared for the new school.

In September, 1905, there appeared in the minutes of the Dover Education Committee for the very first time the words

Dover County School

Headmaster, Mr. F. Whitehouse, M.A.

The staff register records

No. 1 F. Whitehouse 11th September, 1905

No. 2 G. D. Thomas

No. 3 G. W. Coopland

No.4 J. Tomlinson

CHAPTER THREE

The Dover County School

in Ladywell and on Priory Hill

In September, 1905, the County School under Mr. Whitehouse operated in the Ladywell buildings with the sunken room known as “The Well” and beyond that a galleried, larger room where morning assembly was held; further on were laboratories with a “stinks cupboard”.

Also in use, only about 200 yards away, were the premises of St. Hilda’s School, said to be the property of Dover College. The house and garden were entered just above the lower bend on Priory Hill on the west side. Admission to the house was by a rather low door called the guillotine.

Miss Jessie Chapman was in charge here, having been persuaded by Mr. Whitehouse to give up her private school and became Head of the Girls’ Department of the Dover County School. The girls would go down to Ladywell for lessons in art, given by Mr. East and Miss G. Chapman; and Mr. Whitehouse would go to Priory Hill for singing lessons. A lady recollects that he was “very happy” and “he cheered us up”.

The Dover County School had seven forms. Presumably the first form was the preparatory department admitting children from the age of eight. Then there were five forms for girls on Priory Hill and five parallel forms for boys in Ladywell where boys and girls with teacher training ambitions went into 6B and potential university students into 6A. The sixth form boys and girls were based in “The Well” and the galleried room beyond.

Mr. R. C. Wilson, a gentleman still living in 1987, writes that he entered the school in 1905 and left in 1912. He remembers that boys wore red caps with the white horse of Kent over the peak. He adds that “this encouraged the rabble of youth to jeer and shout which caused some unpleasantness, but it ceased when we changed to blue caps.”

There was a united prize-giving in the Town Hall and on one occasion two girls wore academic caps and gowns because they had matriculated. In those days Matriculation and Intermediate B.A. and B.Sc. examinations had to be taken in London.

Reminiscences of the teaching staff in the early years include “Mr. Tomlinson who taught me maths, a subject in which I did not fail again”; Mr. Coopland, who started The Pharos, the school magazine, in 1908; Mr. Frank Smith who taught Latin; Mr. G. D. Thomas, a scientist and scoutmaster; and Mr. W. H. Darby who came in 1908 to teach geography and stayed until 1937. He returned to help the school in Wales from 1940 to 1944.

In the eighty years of the school’s history to the present time there have been only four heads of the geography department and no doubt the same can be said of other departments, just as there have been only four headmasters, all historians. There must be some significance of strength in these remarkable evidences of continuity and contentment. On the other hand there has been a suggestion that teachers have tended to migrate from north-west across the country to the south-east and on reaching Dover there is a tendency to settle.

School teams played at the Danes and the Crabble Athletic ground against such opponents as the Simon Langton School and Harvey Grammar School. Mr. Standring, known as “Scrogger”, who looked after games, was a friendly man and quite a favourite. The girls played hockey and tennis and helped with teas in the pavilion at boys’ cricket matches. The school scout group was very active.

A story is told that Mr. Whitehouse, disciplinarian, gave a boy one hundred lines for some misdemeanour, the lines to be written that afternoon when the boy was due to play soccer in the school team. Mr. Standring pleaded with the head who allowed the lines to be done at another time. The same gentleman who remembers the above story from 1908 also recalls that he wrote a note to a girl and lost the note which was passed to the headmaster. The young man received three strokes of the cane across his palm. He claims that the marks are still visible though probably the imprint is more clearly on the mind than on the hand.

The annual athletic sports meeting, including tug of war and cycle races, often with a military band in attendance, tea and a distinguished lady to present the prizes, was at the Crabble Athletic ground. One gentleman can recall going forward to collect his prize and hearing the headmaster’s sharp instruction, “Take your cap off, boy.” There were also annual swimming sports in the municipal baths on the seafront.

It may help the reader to set these reminiscences in their historical perspective if we recall that this was the time when Dover’s great naval harbour was being completed and Bleriot and the Hon. C. S. Rolls made their historic flights across the Channel.

Something of Mr. Whitehouse’s ambitions for his school may be deduced from his choice as the school song of Forty Years On, until that time the preserve of Harrow School. He also chose Fiat Lux for inspiration and motivation.

The annual salary for Mr. Whitehouse was increased to a maximum of £400 and there were improved salary scales for assistant teachers. Mr. Whitehouse asked for two student teachers at £30 to £35 per annum and this request was sanctioned for one term only. The salary for Miss Chapman remained at £100.

Clearly the years from 1907 to 1910 were troubled by growing pains. Growth was self evident. In 1907, with 101 boys on the register in Ladywell’s shared premises, Mr. Whitehouse was ordered to take in no more. Girls based on Priory Hill began to exceed the number of boys. In 1909 there were 110 boys at Ladywell and 125 girls on Priory Hill, where another house, named Pageant House, was used for a time in addition to St. Hilda’s. There was a waiting list of forty-one children prevented from entry by lack of accommodation. It must be borne in mind that a majority of students paid fees of a few guineas per term. One memory says five guineas was the fee plus a charge for use of books and a small amount for games equipment.

The success of the County School aroused anxieties in both Dover College for boys and the Dover High School for girls in Maison Dieu Road. Dover College initiated discussion on the possibility of a merger but this was not pursued and the High School for Girls went out of business in 1909, making available an attractive school building.

Considerations for the school’s future were brought to a head by controversies in which the Board of Education, Kent County Council and the Dover Corporation fired broadsides that were often acrimonious.

As early as 1905 the town clerk had objected, with committee approval, to the allocation of a separate school number to the Girls’ Department.

Mr. East and his School of Art and Technology were still in the Ladywell building where both the County School and the Art School were increasing their numbers of students. The Borough subcommittee for higher education met under the mayor’s chairmanship and considered the matter of new accommodation for the County School’s boys and girls.

At a conference in the Town Hall in March, 1907, the Kent officials urged separate establishments of boys’ and girls’ schools.

The Board of Education refused to recognise the Dover County School for the years 1907-08 unless there would be a reasonable prospect of new building. This meant instant withholding of grant.

There were minor as well as major financial difficulties. After the 1908 prize-giving K.E.C. declined to pay for the refreshments, so the Dover committee paid the amount and instructed Mr. Whitehouse to discontinue refreshments in future.

In addition to fees of about five pounds per term paid by boys and girls who had not won scholarships, Mr. Whitehouse suggested that bookfees should be six shillings per term in Forms I, II and III and eight shillings for Forms IV, V and VI. Pupil teachers and prospective university entrants should buy their own books. Pupil teachers should not be charged for exercise books. Some parents of girls at Priory Hill objected to the increases and attempted, without success, to start their own rival establishment. Some pupils’ fees remained unpaid but when legal action was threatened all debts were settled. Headmaster was authorised to charge one shilling per term for games requisites.

These details are included to show that the young Mr. Whitehouse and his new school were having a rough ride. He must have been encouraged at Christmas, 1908, when a reunion was arranged in the Town Hall, attended by former students of the Municipal School, the Pupil Teachers’ Centre and the County School. An association of former students was formed. The name Old Pharosians’ Association appears in 1910.

The year 1909 was marked by cross-fire of correspondence. Dover Corporation set up a County School Building Committee which recommended a Dual (Boys and Girls) School to be built on the north-east side of the Dour. Since 1905 the Town Council had paid the product of a penny rate, £550 per annum, to the County School. There were also Board of Education grants, threatened with cancellation if the Board withdrew recognition; K.E.C. payments of about £1,231 and fees from students. In March, 1908, the Borough felt it had paid £1,854 on higher education. The Dover County School was receiving children from outside the Borough so Kent County finance was essentially involved. This was accepted as a principle that applied across the county but in Dover financial matters were particularly pressing because of the need for new buildings.

The words “middle classes” enter into the controversy. The High School for Girls was closing; and if there were not to be good secondary schooling in the Borough the middle classes might move elsewhere. The Borough authorities repeated their proposal for a Dual School in new buildings north-east of the Dour which would be cheaper and better than any extension to existing Ladywell buildings.

There is a letter dated August, 1909, from the Borough’s County School Building Committee with the following words, “The Borough has an estimated population of over 50,000 and will, after the next census in 1911, undoubtedly become a County Borough Temporary arrangements were therefore recommended.

At the end of 1909 Mr. East and Mr. Whitehouse jointly reported that numbers on the register of the County School were 115 boys and 136 girls, with the result that the continued presence of the County School in Ladywell was limiting the work of the School of Art.

In January, 1910, it was proposed to lease the red-brick premises of the former High School for Girls in Maison Dieu Road: and in spite of the Borough’s preference for a Dual School the lease was effected and the girls moved in. The Boys continued in Ladywell as a temporary measure, the junior preparatory school moving to Priory Hill so as to free some room at Ladywell for Mr. East.

These transfers of girls and junior boys are recorded in The Pharos of Easter, 1910. It is not surprising that the next edition in the summer of 1910 begins with the words, “It becomes increasingly difficult for one half of the school to know where the other half is.”

A full inspection of the schools by the Board of Education was held in December with the result that the Board at first re-stated their refusal to recognise existing arrangements as an efficient school. But when the separation of the Girls’ School and the Junior School had been completed the Board paid their grant, back-dated to 1907.

The Borough and the K.E.C. settled down to find a permanent site for the Dover County School for Boys though with prolonged rancour between the two parties.

Mr. Whitehouse and the Borough had throughout favoured a co-educational Dual School. But K.E.C. and the Board of Education wanted separate schools and their financial strength won the argument. The broad intention became adopted for the Borough to lease the necessary land while the County financed the buildings north-east of the Dour.

Mrs. Turnpenny has written, “I was a pupil, aged twelve, of the new County School from 1905. I started in Form 3 and in 1908, with a few other girls, joined a co-educational sixth form at the Boys’ Department. After a year or so, other girls left but I stayed on through Matriculation and Intermediate B.A. and a University Scholarship which I took up in 1912. When the two departments separated into schools on their own I was officially a pupil of the Boys’ School.. . I have never lost interest in it." She has attended recent dinners of the Old Pharosians’ Association in the school hall.

The Pharos dated July 1912 noted that two magazines appeared representing the Boys’ and Girls’ Schools separately. The Pharos records the decision by K.E.C. to spend £5,000 on the purchase of the new site for the Boys’ School. This site was, of course, in Frith Road.

Mr. Whitehouse was at this time appointed Director of Further Education for Dover, the intention being to co-ordinate the flow of school leavers from the two county schools and other schools into continued studies offered by technical and commercial evening classes. He was no doubt encouraged and delighted by the first award of a degree to a girl, now Mrs. Turnpenny, formerly a County School pupil. Two former boy scholars graduated in 1912.

In 1913 the county voted money for the new school buildings and for playing fields off Chalky Lane to be used by both the boys’ and girls’ schools. Plans for the Frith Road buildings were approved.

Prize-giving in the Town Hall was still a joint presentation with reports read both by Miss Chapman and Mr. Whitehouse. Not surprisingly, accommodation in the Hall was taxed to the limit and there is a report of twelve hundred people being present when some got in without tickets and many with tickets could not enter. Headmaster spoke of his school’s “hardy annual problems concerning accommodation difficulties”.

The Pharos commented on the increased number of aeroplanes; new developments in the harbour; and there is even an article on troubles in the Balkans between Turks and Bulgarians that could be a cause of war. Headmaster spoke to the school about the death of Scott and his companions in Antarctica.

Mr. Coopland departed to take up the post as assistant lecturer in mediaeval history at Liverpool University where he later became a professor: and a distinguished physicist named Mr. Schofield came to teach in the school and in evening classes. In 1914 he was appointed principal of the Technical Institute, presumably when Mr. East retired, though we shall again hear of Mr. East in a later year.

The school in 1914 seemed to have little or no premonition of the holocaust to come. Empire Day was celebrated; members of staff got married; the Lord Warden promised to give the prizes; the school was divided into four houses for internal sports; the new playing fields were being levelled and were expected to be ready for use in the autumn. The Old Pharosians formalised their association after a dinner at Dover’s Grand Hotel.

By December, 1914, the school knew that history was “in the making: the school must be one of the nearest English schools to the seat of war, so near that we are within sound of the guns.”

Astonishingly, in spite of the war, builders moved on to the Frith Road site and Mr. Leney, Chairman of Governors, gave finance for a gymnasium. The donor requested that an armoury should be provided for the proposed Cadet Unit. The scout troop disbanded to yield place to military training. An Old Boys’ gathering planned for 30th December was abandoned “owing to the large number of Old Boys who are in the army and navy”. French and Belgian refugees invaded East Kent. The first Old Pharosian casualties were named. Letters from the Front tell of trenches with water sometimes up to a man’s waist. “As fast as the trenches are dug the water comes in. However, we are standing it well,” assured the writer of a letter dated 29th December, 1914.

Forces of land, sea and air surrounded the town. Lists were published of Old Pharosians in the forces. On 3rd December, 1914, the first death of a serving Old Pharosian was recorded.

The school was saddened by the death in 1915 “from a dread disease” of the games master, Mr. R. S. Standring, who had appeared in all the team photos since 1908. He had served the school well and was both loved and respected.

Mr. Tomlinson and others went away on war service. Mr. Taylor, the Borough organist, became the school’s music teacher; and Mr. W. W. Baxter joined the school, soon to be followed by Mr. J. Slater. Both picked up and developed school games within the existing limitations and contributed immensely during the next thirty years to the teaching of French. As young, men they often played in school soccer and cricket teams when playing against adult service teams. Another distinguished arrival on the staff was Mr. W. E. Pearce who was already writing in educational journals on mathematical and scientific subjects.

The Cadet Corps during the war years played a prominent part in the life of the school. The captain and officer commanding was Mr. Whitehouse; in 1915 the other captain was a recent arrival named Mr. Owen Jones, the lieutenants were Messrs. Slater and Pearce while the sergeant-major was Mr. Paddy Pascall, the school’s P.T. Instructor. There were seventy-five cadets in 1915.

The new school playing fields and the Danes ground were taken over by the army; the gymnasium could not be built until after the war; and some of the school’s engineering machinery was taken away for making munitions. Boys made periscopes which went to the trenches and a letter of thanks came from a colonel in France.

Mr. Tunnell, Mr. Pearce and Mr. Owen Jones were called away to war service, Mr. Pearce taking his scientific knowledge and teaching skills to a naval training station at Devonport. Mr. Slater arranged cadet exercises and an Old Pharoslan - on the Somme wrote a requiem for a sergeant in the R.A.M.C. Some boys made bandages and other

hospital materials. Six more Old Boys were killed-in action, four of them officers. Some were “invalided Out”, particularly for damage due to gas. At least one Military Cross was gained.

Mr. Slater continued as prime mover in the cadets and in what limited games could be played at Crabbie or at the Elms Vale ground. He played for the school XI against the Old Boys; but he did not play in a cricket match between fathers and sons when eleven fathers scored 101 and eighteen sons batted until their total reached 102.

In October, 1916, the school entered the Frith Road buildings. It must have seemed like arriving in the promised land after years of wandering and uncertainty. An appreciative youth described how the concrete floors of Ladywell had been replaced by Frith Road’s resplendent floors of polished wood. Some of the rooms were made dark by enveloping sandbag protection.

Reference may be made to bound volumes 1 (1908-13) and 2 (1914-18) of The Pharos kept at school.

CHAPTER FOUR

The School in Frith Road

October 1916 to December 1931

Because of the war there was no formal opening of the new buildings. The Annual Prize Distribution was cancelled but parents were invited to an “At Home” early in December. Alas, it had to be abandoned for reasons of war-time economy. Boys helped to dig up the playing fields to grow vegetables, some of the produce going to the hospital.

As male teachers were called away lady teachers took their places. One French boy in the school learned that his father had died fighting in the French army “pour la défense de la France et de l’humanité”. In school a weekly collection was made for Dover prisoners of war.

Mr. Clatworthy and Mr. Darby went on military service, followed by Mr. Baxter and three others. Among the ladies replacing them were Mrs. Clatworthy, a classicist and the legendary Miss O. M. Rookwood.

Letters poured in from serving Old Pharosians in training and in action from many parts of the world. One man training in the Artists Rifles reported that the instructors “unfortunately make no attempt to confine any sentence to words found in the dictionary”. The horror of war and the chivalry of man may be illustrated by the report of one Old Pharosian. A bullet passed through his cheek, smashing his teeth and jaw but his face was rebuilt in a German hospital.

More lady teachers arrived so that young boys were cared for and bigger boys could take their examinations. House matches were played when possible and at other times boys and teachers worked on the land. Everything was liable to interruption when the siren sounded the alarm for air raids.

Mr. Darby, geographer, was engaged in meteorological work in France; Mr. Baxter went to Cranwell; Mr. Tunnell had been in the thick of things at the front but was recalled to be trained for a commission. He returned to France and, alas, the following entry, like so many others, appears in The Pharos:

KILLED IN ACTION

TUNNELL, OLIVER

2nd Lieutenant, Northumberland Fusiliers

24th October, 1918

Having been in front-line action through most of the war he was killed within three weeks of the Armistice.

There is, of course, in the present school a window bearing the names of those Old Pharosians who lost their lives in the 1914-18 war.

As men came home for demobilisation they called at school in khaki or navy uniforms, the schoolmasters hoping soon to return to their academic gowns that were worn in class until after the Second World War.

On Monday, 11th November, 1918, the school heard the siren sound at 11.00 a.m. to mark the end of the war. The school ceased work and went into town and the seafront for general festivities. Flags hung from the houses, church bells pealed across the town and the night sky was lit by fireworks saved for the celebration.

Corporation workmen removed sandbags from the school buildings as peace on earth was proclaimed. Of the 224 Old Pharosians who had served, 31 had given their lives.

Among the masters who returned to the school were Mr. Tomlinson, Mr. Pearce, Mr. Baxter and Mr. Darby. Mr. “Ferdie” Allin arrived as a new master, to remain as a most effective teacher of Latin and master in charge of games.

He took the place of Mrs. Clatworthy who died and whose husband endowed Latin prizes in her memory. Other ladies departed with the exception of Miss Rookwood who was to make her life’s work in the Junior School.

Mr. S. F. Willis was another new master who returned from the Machine Gun Corps and took command of the Cadet Corps with Mr. Pearce as lieutenant. Mr. Willis taught history and music until 1949 and then part-time until 1952.

In 1919, as games returned to normal, the four houses adopted the names that they bore for many years, boys at that time being allocated to Maxton, Buckland, Town or Country on the geographical location of their homes.

The juniors had moved to Frith Road with their seniors in 1916 but post-war increase of numbers led to a return of junior boys to Priory Hill under Mr. Willis. The total County School enrolment was about 300; and parents were advised that the best chance of admission was through the Junior School for boys aged between eight and eleven years. In 1920 there were seventy-seven boys crowded into St. Hllda’s on Priory Hill.

School matches returned to their pre-war status and in the Harvey Grammar School cricket XI the name of L. Ames appears. The Old Pharosians formed a cricket club, Mr. J. Slater heading both the batting and the bowling averages.

The operetta Merrie England was performed in the Town Hall. Among the soloists we find F. Whitehouse.

An Old Pharosian soccer team entered a local league and continued to do so until the Second World War. The annual dinner and a New Year Dance, arranged jointly with the Old Girls’ Association, became part of the Old Pharosian calendar.

The school continued to grow in numbers and the headmaster wrote, “These arrangements, however, are to be regarded as a solution only for the next four or five years, at the end of which a larger scheme will doubtless have matured.” Perhaps in the headmaster’s mind there was already a perception of the limitations at Priory Hill, an awareness of noise of increased traffic in Frith Road and the disadvantage of remote playing fields. He could foresee the coming expansion of population and higher education.

London Matriculation could now be taken in Dover and there was increased interest in commercial subjects, notably economics. In 1920 the school experienced a general inspection by H.M. Inspectors who devoted special attention to science and mathematics. One result was the division of the sixth form into an Arts side and a Science side. On the Arts side it is recorded that Mr. Baxter gained an M.A. and introduced Franco-British exchanges.

On the 14th July, 1920, at Crabble L. Ames of the Harvey Grammar School scored 101 not out, the first recording of a century in the pages of The Pharos. At Frith Road there were facilities for fives and rackets so these were added to football, cricket, athletics and swimming in inter-house competitions. The Junior School had its own football and cricket teams, literary competitions and concerts.

Accommodation problems were painfully reactivated when the landlords of St. Hilda’s gave notice that they wanted the building. Accordingly the Junior School transferred to Ladywell with Mr. George Devenish Thomas in charge. What long and excellent service this gentleman gave to the school!

In 1921 the staff was further strengthened for many years to come by the arrival of Messrs. E. S. Allen, L. W. Langley, A. B. Constable, E. Froude and T. Watt, followed soon by W. Uncles. These men all stayed until at least the Second World War; and they were joined in 1924 by Mr. T. E. Archer and in 1928 by Mr. A. E. Coulson. Both these masters stayed in continuous service to the school for over forty years.

In October, 1921, Mr. and Mrs. Whitehouse held an “At Home” mainly for parents. Mr. Whitehouse referred to difficulties caused by the continued occupation by the army of the school playing field; and by the separation of the Junior School in Ladywell, now under Mr. Langley. The headmaster hoped that the K.E.C. would “see their way clear to procuring land for new buildings before long”.

In 1922 there were several indications of further post-war revival. The playing field and the town’s swimming bath came back into use. A Parents’ Association was formed; and a Town Hall prizegiving gave the head the opportunity to report that school numbers had already outgrown the accommodation provided in 1916 at Frith Road. A prize for geography went to R. A. Pelham who became a doctorate lecturer in the department of geography at Southampton University. He always declared his debt to Mr. Darby. A Literary and Scientific Society was started. A visit was made to Leney’s brewery. The first Old Pharosian obtained an Oxford degree; more boys stayed on in the sixth form; another boy was the first to go to Cambridge. Academic successes warranted the positioning of the first honours board. Among the new entrants in 1923 was W. F. Kemp, now a canon of Canterbury Cathedral living in the Precincts, and L. C. Sparham who became a missionary and schoolmaster in East Africa and there lost his life.

There was an active Association of London Old Pharosians who visited the House of Commons and arranged varied social occasions. The Association as a whole numbered about a hundred with Mr. Whitehouse always their president. He suffered some ill-health in 1923 but made a good recovery. He presided at a London Old Pharoslan Dinner and Miss Chapman replied to the toast for “The Ladies”.

By the end of 1923 the difficulties of a growing school split in separate buildings caused Mr. Whitehouse to persuade the Kent Education Committee, where he had much influence, to agree to move the school yet again to available space on Astor Avenue. On 6th March, 1924, the whole school assembled on what is now the Lower Field to watch Canon Elnor, Chairman of the Governors, cut the first sod.

The Dover County School for Boys was to move as one body to a new site with a new building accompanied by its own playing fields. The Frith Road premises would be left to the Girls’ School who were still in the small building in Maison Dieu Road: and Ladywell could be left for the sole use of the Technical College.

At the Astor Avenue site Mr. Hugh Leney, so long a generous benefactor, gave an additional field known for all time as “Leney’s” and he again gave money for the gymnasium.

K.E.C. even reduced fees from £15 a year to £12 which encouraged requests for admission. The general relationship was that two fee-paying places could be offered for every entry by scholarship. In 1925 for the first time the school roll exceeded four hundred. Twenty-five boys entered with scholarships from Dover, Deal and district.

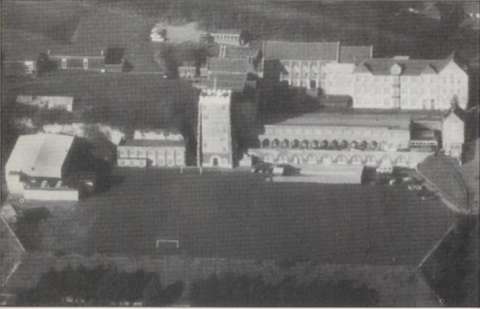

Plans drawn for the new buildings showed, in the headmaster’s words, that the school would “suitably match the historic Castle on the other side of the valley”.

It is pleasant to record that Mr. W. H. East who was Head of the Technical School and the Municipal School before 1905 when Mr. Whitehouse took charge of the newly formed Dover County School, now in 1926 makes a re-appearance in our history. He was a school governor and Mayor of Dover, in which capacity he attended the Town Hall prize-giving and presented the East Cup which is still in the school’s trophy cupboard. Alas, Mr. East died in the following year.

Headmasters have to be fund-raisers and the impending construction of the new buildings led to massive operations to finance an organ for the new school hall. The year 1926 gave opportunity for the school’s 21st Birthday celebrations and the headmaster suggested “birthday gifts”, an idea that yielded £500. There was a church service of thanksgiving in St. Mary’s, to which the Mayor and Corporation and the school processed from the Town Hall; and at which the Headmaster of Eton preached. All returned to the Maison Dieu Hall for tea; and a photograph shows that many of the boys wore hard “Eton” collars. A dance followed in the evening, at the end of which some Old Pharosians “seized the great little man and bore him shoulder high down the hall”.

Mr. George Devenish Thomas, who appeared as No. 2 on the staff register in 1905, retired through ill-health in 1927 and died in 1928. By his science teaching, his active leadership of scouting and his willing participation in many activities he held the affection and respect of boys for more than twenty years. He had been, since 1916, Assistant Principal for Further Education in Dover. The Thomas Scholarship still enables boys from the school to go to Bristol University.

A musical society was formed, the library stock of books increased in number and in use; and plans for the new school buildings were viewed with admiration and anticipation.

C. G. J. Jarrett had been winning merit awards and prizes all the way up the school and he now departed with a state scholarship and a major scholarship to Sydney Sussex College, Cambridge. In 1930 Mr. Whitehouse was able to visit Cambridge and be entertained to dinner by Old Pharosians Sanders, Garland, Stanway, Dilnot, Carpenter, Trist and Jarrett. Jarrett rose through the Civil Service to become Sir Clifford Jarrett, K.B.E., permanent secretary or under-secretary to several ministries until he retired in 1970 and then for nine years often visited Dover and the school when he was Chairman of Dover Harbour Board.

When Mr. Whitehouse dined in Cambridge with his former scholars he was able to tell them of the new school buildings and fields. Levelling had been completed and some estimates have been made that this work cost about one third of the total. Lower and upper fields were grassed and prepared for use. Indeed, cricket was played at Astor Avenue from 1929 and soccer from 1930.

A school bazaar in the Town Hall raised a further £355 to add to an existing sum of £600 for the organ. Very few state schools enjoy such a privileged possession. The contract for building the school went to Claysons of Lyminge and they began building in 1929.

Impatience for the new buildings was increased by acute discomfort and unease at Ladywell where furniture of appropriate size for junior boys was inappropriate for mature evening students.

In November, 1929, the sixth form was visited by two inspectors. There were about seventy boys divided into sections studying science, arts, engineering and commerce. This was the year of the financial crash on Wall Street whose repercussions were to increase the scourge of unemployment throughout the following decade. Mr. Whitehouse was clearly concerned about jobs for his boys and the words “vocational guidance” are used for the first time and remain with us for all time.

Mr. A. E. Coulson had joined the school in 1928 and stayed until 1971, a continuous period covering forty-three years that included war-time in Wales. Since retiring he has gained a high reputation in the field of computing and has been honoured by the University of Kent at Canterbury. Mr. F. Kendall arrived in 1931 and now lives after retirement in 1965 at Bury St. Edmunds.

The years close to 1930 seem to have been noted for success not only in academic achievements but also in games. On the cricket field J. A. Paterson and W. M. E. White were prominent. The latter played for Cambridge University, Northants and the Army. In the 1931 school XI he scored two centuries and took many wickets. We have reason to believe that, past the age of seventy, he still plays in his retirement on the Isle of Guernsey. In 1930 seven records were broken in the athletic sports, with R. P. Peyton and L. Goodfellow outstanding. The former was senior champion in three successive years; while L. Goodfellow was also an outstanding swimmer. J. A. Paterson added to his cricket prowess by captaining a very successful soccer team. He became a good schoolmaster, a teacher of languages and cricket in Lancashire where he is now in retirement. The Pharos contains a pen and ink drawing of J. A. Paterson, “The Captain”. Another outstanding soccer player of this time was A. Salmon who went on to Sandhurst and later played for the Army. The name of E. Crush, later to play for Kent in the post-war years, begins to appear as a young cricketer of promise.

Mr. W. E. Pearce must have been very busy at this time. The science laboratories in the new school benefited from his advice: he was officer commanding the cadet corps; he, with Mr. Archer, confirmed rugby football as a major school game; and he was working on his first book, School Physics, which was published in 1935 and, with other text-books that followed, made him famous as a science teacher throughout the land. In 1938 when Mr. Tomlinson retired, Mr. Pearce became deputy headmaster and supported Mr. Booth in war-time in Ebbw Vale and then in the post-war return to Dover.

Our history has brought us to the autumn term of 1931, described in a Pharos editorial as “the most important term in the history of the school”.

Term started in September and on the first Saturday Canon Elnor and the Headmaster held an “At Home” for parents to be shown round the buildings by their sons.

School life proceeded, Speech Day came and went and on Wednesday, 9th December, came the day of days when Prince George, Duke of Kent, came to declare the school ceremonially open. Boys and masters processed from Town Hall to St. Mary’s Church where the Bishop of Dover preached on tradition and the future. Everyone returned to school and the cadet corps formed a guard of honour and sounded a royal salute. Lunch was taken in the dining hall in the company of many distinguished visitors. After lunch the Duke addressed the assembled school in the Great Hall. Hugh Newman made a speech of welcome on behalf of the school.

An Old Boy who signed himself “Nineteen hundred and nine” and who had served in the 1914-18 war wrote as follows:-

“Today’s ceremony marks a culminating point of Mr. Whitehouse’s headship. He has watched over successive generations of boys for over twenty-five years; he has scolded them, encouraged them, helped them and seen them grow to manhood; he continues to watch their careers with almost parental pride; he has seen the school grow to its present dimensions and importance, and he is in the proud and enviable position, thoroughly merited, of seeing it now housed under almost ultra-modern educational conditions, with a fine and ever-increasing tradition, and can well and truly feel that his life’s work has come to a wonderful fruition, a privilege accorded to few men.

One can add little to this tribute by someone who knew Mr. Whitehouse and admired him as “the great littleman”.

Mr. Whitehouse is reputed to have said that in 1905 he was “in the right place at the right time”. He was certainly the right man for building a school, a man of vision, energy and determination.

He was a member of Kent Education Committee, Chairman of the Scholarship Examination Committee, President of the Head Teachers’ Conference, recognised by the town with the Honorary Freedom of the Ancient Port and Borough of Dover.

Mrs. Whitehouse supported him all the day long of his troublous life, most notably in the “At Home” hospitalities every October.

In 1905 the school had started with some four teachers and perhaps fifty students. In 1931 the headmaster had a teaching staff of twenty-four; fifty-seven boys in the sixth form, divided into Six Arts, Science, Commerce and Industry; seventy boys in the fifth forms and comparable numbers in each of the four forma below. Finally there were fifty young aspirants in the Preparatory and Transitional forms under the firm care of Miss Rookwood.

The way had not been easy. Beginning in shared premises, working under conflicting authorities, emerging through war-time into the school’s own buildings and soon outgrowing that shell to emerge on the sometimes sunlit uplands where the school flourishes today and looks with confidence to its future.

Postscript

Looking down the names of boys who were in the school in 1931 there are many who served in the Second World War when Herr Hitler threatened the world with violence, domination and genocide. Some gave their lives and their names are recorded in a book of remembrance that accompanies the memorial to those who fell in the First World War.

Some men who passed through the school have gained this world’s honours in service to the state, the armed forces, the church, in education, commerce, industry and other walks of life. Some names on the registers recur as fathers begat sons and were pleased to get their boys into their school on the hill.

In 1936 Mr. Whitehouse retired and handed the headship to Mr. J. C. Booth who, with steadfast support from Mrs. Booth, saw the school through the war years in Wales, brought it back to Dover and renewed its strength until in 1960 he in his turn retired to be replaced by Dr. Michael Hinton. A wind of change swept through the school for eight years, to be consolidated and advanced from 1968 to the present time by Mr. R. C. Colman, with whom it is a pleasure to work.

Each of the four headmasters received his education at a grammar school and was an Oxbridge historian. Each has drawn strength from Christian belief and practice. The present headmaster likes to speak of the family of the school’s succeeding generations. He has chosen to regard as Old Pharosians all who have ever passed through the school. Of these, some six hundred choose to belong to the Old Pharosians’ Association whose main purpose is to sustain and preserve the school that served them so well.

Let there be light, forty years on and into the future beyond our time and vision.

The School today (1987), though the sports hall on the left belongs to Astor Secondary School.

Reference may be made to the bound volumes 3, 4 and 5 of The Pharos and the Diamond Jubilee issue of 1965-66 kept at school.